Katrina,

1 year later - Heroes of Mariah

Searching for the Face of Katrina and a Sign

of Hope

To a reporter covering the aftermath, a girl

named Justice became a symbol of the suffering. Where was she? In a place

that felt like home?

By Scott Gold, Times Staff Writer

August 28, 2006

New Orleans The first time I met Justice, she

was in the Louisiana Superdome, sitting sidesaddle on her mother's lap

and swinging her legs as if she were on a shady porch, not trapped in a

defeated city.

At the time, two days after Hurricane Katrina

struck, she was 17 months old, the same age as my daughter. I wrote about

her that night, how she was eating trail mix rescuers had handed out, how

I had foolishly advised her mother when there was nothing else to eat

that babies shouldn't eat raisins.

She became, to me, the face of the storm, the

face I saw when I thought about everything the Gulf Coast had endured in

those terrible months: the decimation of 93,000 square miles, the dead

and the displaced, the unmasking of a forgotten American underclass. Did

her family, like many who endured the hurricane, still live with a quiet

sadness? Where had they ended up? Wherever it was, did it feel like home?

As the first anniversary of the storm approached, I decided to find out.

There are suggestions of progress and recovery

here. Billions of dollars in federal aid is headed toward the region. Some

have suggested that New Orleans, long one of the poorest cities in America,

could become a boomtown. But it's easy to be pessimistic about its future.

Block after block remains abandoned. Crime is

up. Suicides have tripled. City Hall where the facade is still missing

some of the letters in "City Hall" announced recently that the anniversary

of Katrina would be marked with comedy and fireworks. But there is a pervasive

sense that the party is over, and amid public outcry, a more somber memorial

has been planned.

Maybe, I thought, finding Justice would provide

some hope.

The operator at the Federal Emergency Management

Agency was reading from a script: "What state did your disaster occur in?"

I told her that it was wasn't exactly my disaster but that it had occurred

in Louisiana, that I was trying to locate a family I had last seen in the

Superdome.

She suggested calling the Louisiana Family Assistance

Center and the National Next of Kin Registry.

The center said it would need an address, phone

number and date of birth, which, I pointed out, if I'd had, I wouldn't

have had to call in the first place.

The registry operator said: "I can't even tell

you where to start."

Next was City Hall in New Orleans. The operator

offered a number for the Red Cross; it was a fax line. I called back to

City Hall.

"Have you tried FEMA?"

The only concrete leads were on a list of addresses

compiled from voting and property records where Justice's family may

have lived before the storm. The first stop was a house in the working-class

Bywater district. One of Justice's relatives appeared to have lived in

this "double," a fatter version of the city's narrow shotgun homes.

Azaleas had taken over, and weeds had erupted

through the concrete steps leading to the door. There was no one home,

hardly unusual in a city where fewer than half the residents have returned.

Across the bridge that spans the nearby Industrial

Canal, a scrawny man was wrestling the radiator out of a green pickup on

the roadside. The truck had been struck by a tidal surge that had ripped

off its roof. But in New Orleans, where scavengers pick through the rubble

every day, it was a find. His hands coated in rust, sweat dripping from

his nose, Tyrone Smith said the radiator might fetch $15 or more at the

scrap yard.

Smith put in 13 years at a shrimp plant before

the storm a job that vanished amid a crumbling economy. Now he gets $10

an hour rewiring flooded houses. The 42-year-old lives in a gutted house

in the 9th Ward, and sleeps in a bunk bed next to exposed studs pocked

with rusty nails.

A pickup truck rumbled down the street. It was

a noisy arrival; clamshells swept in from the Gulf of Mexico still covered

many of the streets. "The bossman!" Smith said. He raced off to retrieve

the kneepads his boss had given him for work. Then he ran toward the truck,

pausing only when he spotted a twisted piece of aluminum lying in the weeds.

It was enough, he said, to get a couple bucks at the scrap yard.

House after house was vacant. No one remembered

Justice or her family.

Next to one of the houses in the Bywater, neighbor

Dymous Henry said seven people were living on the block of 21 dwellings.

Even those who have returned, he said, are not really home.

"People here can't take change," said Henry, 48.

"There were people who lived in this part of town who had never been Uptown,

never been across the river. This has done something to them. Everybody's

changed."

In the Gentilly neighborhood, close to Lake Pontchartrain,

was a house where Justice's mother, Tonisha, may have lived in 2002. Now,

a meaty tree limb juts through the roof. The block is so quiet you can

hear the warped houses wheeze as they settle.

Across the street were the block's only residents.

Renee Daw, 43, who works at a shipping warehouse, and her son, Raynau,

8, rode out the storm at home. When they were chased from the attic because

the water got so high, they kicked out a vent and climbed onto the roof.

They were rescued after three days. They returned in April, and live in

a FEMA trailer parked in front of their gutted house.

New Orleans is not an easy place to be a kid these

days. There are two boys Raynau's age three blocks away. They came by to

play, once. The local park is padlocked; the bleachers next to the baseball

diamond are upside-down. Asked what he was going to do with the rest of

his day, Raynau just shrugged.

"We mostly just stay in the trailer," Daw said.

"We're inside people now."

Raynau misses the black Labrador he had to leave

behind when he and his mother were rescued. Other than that, he never brings

up the storm, even though they still boil water to brush their teeth, even

though a lifejacket, a remnant of the rescue, still dangles from the rafters

of the attic.

"He's let it go," Daw said. "Just like his mama."

In Pontchartrain Park, a neighborhood of postal

workers and schoolteachers that was devastated by a breach in the London

Avenue Canal, property records indicated that Tonisha's mother, Winifred

Jones, owned a tiny home. Today, the door is missing. There is nothing

inside but a toilet and a bathtub full of chunks of drywall.

Down the street, a man living in a FEMA trailer

was mowing a neighbor's lawn, not because he had any neighbors, but because

snakes and other critters had taken up in the overgrown lots.

"Tonisha?" he said. "That's my goddaughter!"

This was Winifred Jones' house, he confirmed.

But when asked where they were living, he snapped: "Why are you asking

me all these questions?"

He began to sweat profusely. He grabbed the sides

of his baseball cap, pulled it low and retreated into the street, stumbling

over a pile of empty bleach bottles, tree limbs and splintered boards.

"Do you know them?" he shouted. "Or don't you?"

It was a valid question; despite the connection

that I felt with Justice and her mother, I didn't really know them at all.

"I don't mean any harm. I'm just trying to see if they're OK."

"Don't you get it, boy?" he screamed. "Everybody's

gone! Everybody's lost!"

Twenty-two houses, in Gentilly, in Pontchartrain

Park, in the Bywater. Nothing. Fifty-three phone calls, to FEMA, to City

Hall, to disconnected numbers, and to people in North Carolina and Oklahoma

who appeared to be relatives or old neighbors, but none knew Justice and

the family.

Where were they?

An Internet message board set up to reunite storm

victims provided a clue I had missed: a note from Winifred Jones written

from the Houston Astrodome, which after Katrina had served as a shelter.

It included a cellphone number.

A recording said the phone network would not accept

messages. Another dead end, it seemed. But a few minutes later, my phone

rang. A woman was on the other end: "Who called this number?"

"I'm trying to find Tonisha Jones," I said.

"I'm her auntie," she said. She said they were

living in Beaumont, Texas. "I'll have her call you in 15 minutes."

When the phone rang, I raced across the room to

answer it. I said I was looking for a little girl named Justice.

"That's my baby," Tonisha said. "I remember you."

The next morning, Justice was on the second-floor

balcony of a tidy apartment complex on the west side of Beaumont, swinging

around her mother's leg, a smile on her face, her red gingham dress billowing

behind her.

There were suggestions of home. A scooter was

outside the apartment and, inside, a chicken was baking in the oven. Justice's

father, Joshua Lonzo, was tying on an apron getting ready to go to work

at a grocery store.

But like half a million evacuees who remain scattered

across the country, Justice's family is still unsettled. Nothing feels

familiar. They are still learning their way around the area. The stores

don't carry the Cajun spices they had cooked with, or the white Bunny Bread

they had used for sandwiches. Dinner is eaten on donated plates, in front

of a donated TV.

Tonisha and Joshua Lonzo she has recently taken

his last name were products of the New Orleans projects. Gangs ruled.

Drugs were everywhere. As a boy, Josh watched more than one man get shot

in the head. Only God, he says, knows how he and Tonisha chose the straight

path.

They met at a party when they were 15. They lived

across the railroad tracks from each other and went to different high schools

but saw each other every day. Their friends joked that they had turned

into an old married couple before their senior prom.

Four years ago, they had their first daughter,

Taylor. They married a short time later. Tonisha worked as a cashier at

a drugstore. Josh was a cook on a riverboat and drove a truck for an upholstery

company.

"We were poor," said Tonisha, 25. "But we were

making it."

They rented a little clapboard house in the 7th

Ward. They bought a bedroom set on layaway. They went into the French Quarter

for an occasional daiquiri and stopped by her grandmother's house on weekends

for a slice of coconut pie.

On the day the storm came, they gave no thought

to leaving the city, like tens of thousands of others. Generations of their

family had stayed and ridden out storms and, in any case, they had little

money and nowhere to go.

They went to the Superdome better prepared than

most. They had crackers, sardines, smoked sausage. They had three changes

of clothes for the girls and 25 diapers for Justice.

By the time they got out six days later, everything

that had not been lost or stolen a couple of boxed meals, some medicine,

keys to a Dodge Intrepid they would never see again fit into a child's

suitcase decorated with the Cat in the Hat. The girls were covered in mud

and urine. They had lost their shoes, so Tonisha had made them new ones,

first by tying plastic bags around their feet, then by tearing strips of

fabric from a pair of pants someone gave her.

When a military helicopter flew them to Louis

Armstrong New Orleans International Airport, Tonisha saw the flooded city.

"I looked one way water. I looked the other way water. I couldn't believe

my eyes," she said. "We had no idea what had happened."

The next day, a Navy plane flew them to Corpus

Christi, Texas. After three weeks at a shelter, Tonisha got in touch with

her aunt, Galintha Harden, who had also ended up in Texas. Her aunt told

her about an apartment in Beaumont that a church had found for another

relative, so Tonisha, Josh and the girls took a bus there.

Days after their arrival, Hurricane Rita slammed

into the city. "The double whammy," Tonisha said. They fled again, 11 relatives

in two cars. They stayed in a hotel in Lafayette, La., for two weeks.

Those were dark days. They were exhausted. Tonisha

could not shake the putrid smell of the Superdome.

"I was crazy," she said. "I just kept smelling

it, no matter how much we washed. I would sit and cry, cry, cry. Eventually,

I realized that I had to stay strong for my kids. I realized that it could

have been worse, because we were alive."

In October, Tonisha, Josh, the girls and three

other relatives moved into the $550-a-month two-bedroom apartment in Beaumont.

By then, Tonisha had discovered she was three months pregnant.

It was not an easy pregnancy; doctors hospitalized

her for two months because her amniotic fluid was too low and her blood

pressure too high. Josh had found work as an automotive technician. But

juggling the girls' care and his job proved too much. After he was late

to work a couple of times even after bringing a note from Tonisha's doctor

explaining that she was in the hospital he was fired.

They were so strapped for money that at one point

they borrowed a car and drove 260 miles to New Orleans to recover $240

in cash that Tonisha remembered she had left in the pocket of Josh's jeans.

The money was with the electric bill that Josh was supposed to have dropped

off that week.

Looters had already been inside their house but

had missed the envelope. Tonisha washed the mold off each bill with soap

and water.

While there, they salvaged what they could.

Some of Josh's trading cards survived, including

an autographed Brett Favre football card he had wrapped in plastic. Tonisha

recovered a bag of photos that had been on top of a bookshelf. Inside was

the only record of their old life photos of prom night, he in a tux and

she in a silver gown, and of Taylor at her first birthday party, a handful

of dollar bills pinned to her shirt in a New Orleans tradition.

They miss New Orleans the pickled meat and the

gumbo, the raucous parades held by the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club.

"But it's peaceful here," Tonisha said one recent afternoon, as her girls

ran through the courtyard of their apartment complex and pretended to make

spaghetti with a pile of twigs.

Justice is a typical toddler, "always looking

for trouble," Tonisha said. She gets mad when told she cannot store her

toys in the microwave. She is scared of bugs and loud noises. She uses

a broomstick to flip on the lights. She is too little to remember the storm,

or New Orleans. Tonisha figures that's for the best.

Zoey, the baby, was born in April. She sleeps

between Tonisha and Josh. Justice and Taylor sleep in a single bed on the

other side of a nightstand crowded with sippy cups, toys and the Bible

that Tonisha and Josh recently bought to replace the one they lost in the

flood.

Earlier this month, 10 months after Tonisha applied,

FEMA gave them $10,000 to cover the contents of their house. They have

received a bit of additional aid, from the Red Cross and from a local church.

They have no health insurance; the children are covered through Medicaid.

Josh, 24, has a new job working at the deli of a grocery store. He makes

$7.80 an hour. The three paychecks that come into the apartment are pooled;

they total about $700 a week, which pays for rent, bills and food for eight,

but not much more.

On July 4, Tonisha's aunt was driving the car

they all shared when she was rear-ended by a woman with no insurance. The

girls' car seats had been stored in the trunk, which was so badly damaged

they couldn't get in to retrieve them.

Tonisha and Josh needed a car of their own. Josh

found an ad asking $4,500 for a 1997 Chevrolet Suburban. It was big enough

for all of them, but the purchase would sap about a third of their net

worth and the car had nearly 200,000 miles on it.

Tonisha and Josh borrowed her aunt's crumpled

car and drove to the seller's house in a middle-class neighborhood. Josh

hopped out to take a look. "What do you think?" he asked when he came back.

"It's up to you," Tonisha told him.

Josh took the Suburban for a spin. The seller

told him that it had a new transmission and air conditioner. Josh paid,

in cash, and drove it home.

"I just hope it lasts," Tonisha said as she pulled

out behind him.

Justice had been in the car for a while, and was

getting antsy. Without the car seats, she and Taylor were not strapped

in: Taylor was sitting on top of a case of bottled water, and Justice scooted

over to the window to peer out.

"Justice!" Tonisha yelled. "Get away from the

door! You want to get hurt?" Justice slouched in the back seat and pouted.

Tonisha fiddled with the radio, trying to distract her so she wouldn't

cry. "Justice!" she called. "It's your song!"

It was Mariah Carey's "Fly Like a Bird." The song

is a prayer for strength: "Don't let the world break me tonight

. I pray

you'll come and carry me home." Justice bobbed her head to the beat, her

braids swaying back and forth. Then she put her head on my shoulder and

her hand on my arm. Soon, she was asleep.

I stared out the window, thinking about the storm,

about everything I'd seen in the last year, about how silly it had been

to think that a 2-year-old would be able to provide me with a happy ending.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Gold has covered Hurricanes Katrina and Rita

and their aftermaths for the last year.

Click to enlarge.

Pic 1: A new start: Justice

Lonzo, 2, lies next to her older sister in a two-bedroom apartment in Beaumont,

Texas, where they live with their parents, a baby sister and three other

relatives.

Pic 2: "We're inside people

now": Renee Daw, 43, looks at debris left near her home in New Orleans'

Gentilly

neighborhood. She and her 8-year-old son, who

have lived in a FEMA trailer in front of their damaged house since April,

are the only residents on their block. "We mostly just stay in the trailer,"

she says.

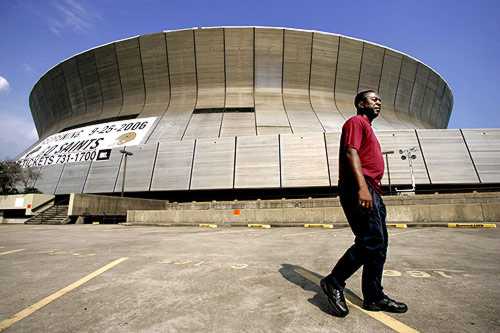

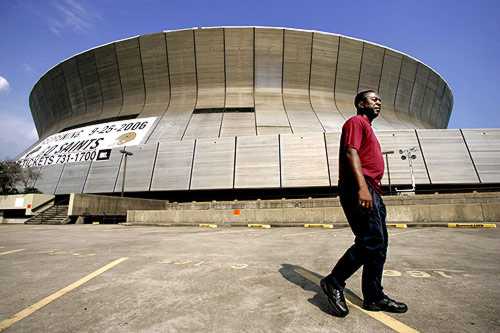

Pic 3: "Everybody's changed":

Dymous Henry, 48, walks in front of the Superdome in New Orleans. He says

that even people who have returned to his neighborhood are not really home.

"This has done something to them," he says.

Pic 4: Life after the storm:

Tyrone Smith, 42, rests inside a gutted house in the 9th Ward. Before Hurricane

Katrina, he

worked at a shrimp plant; now he gets $10 an

hour rewiring flooded homes.

Pic 5: Homesick: Tonisha

Lonzo, 25, and Justice walk up to their Texas apartment. The Lonzos still

feel unsettled a year after Katrina uprooted them from their New Orleans

home. They eat dinner on donated plates, in front of a donated TV.

Pic 6: Face of Katrina:

Justice Lonzo, 2, gets into the family car to pick up her sister from school.

Reporter Scott Gold met Justice at the Superdome in Katrina's aftermath

when she was 17 months old.

Source: KTLA

(All rights reserved)

Posted on August the 29th. 2006

Copyrights and all rights are reserved to the owner of the rights.

Site owner: Gilles Ollevier

Heroes of Mariah 2000

E-mail: staff@heroesofmariah.com

Index